This month’s blog post is from guest contributor Prof. Rachel Murray. She is a Professor of International Human Rights Law and Director of the Human Rights Implementation Centre, University of Bristol Law School, UK (Rachel.murray@bristol.ac.uk). Her contribution is linked to a larger project on the implementation of judgements of human rights courts. We are incredibly grateful that she has agreed to share her insights here on the Monitor and with our readership!

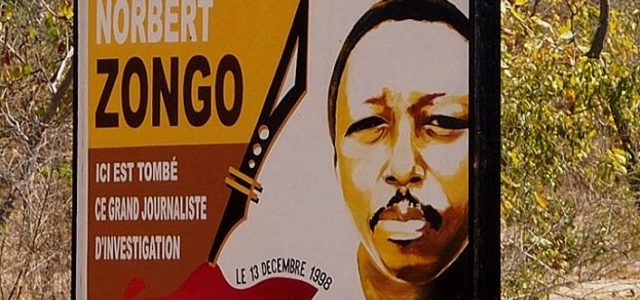

Photo: Poster related to the case of Norbert Zongo in Burkina Faso (Credit: Ignace Ismaël NABOLE, obtained via Burkina24.com)

The African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (‘African Court’), in finalising cases, has made a range of orders providing reparations for victims of the violations found. These have included the payment of compensation (Zongo et al v Burkina Faso, Ruling on Reparations, para 111), release of an individual from detention (e.g. Alex Thomas v Tanzania, Interpretation of Judgement), as well as guarantees of non-repetition, such as amendment of legislation (e.g. Konaté v Burkina Faso, para 176(8)). Some have been very specific, others more general (e.g. ‘Orders the Respondent State to amend the impugned law, harmonise its laws with the international instruments, and take appropriate measures to bring an end to the violations established’ (APDF and IHRDA v Mali, para 135(x)). Yet, to what extent do the State authorities implement these orders? The African Court has so far chosen to take a light-touch approach to monitoring implementation of its own judgments. It publishes in its activity reports information on what measures the State has taken with respect to each reparation ordered in the judgment or ruling in a simple table format (Activity Report of the African Court 2018, para 18). Whilst this is useful in keeping track of what the State has done it does not use this to make any assessment on the extent to which it considers such measures to be satisfactory or not. Rather, in only limited circumstances has it taken further action to make such an evaluation (Interim Report of the African Court on Non-Compliance). According to the Protocol establishing the Court, the African Court is to ‘submit to each regular session of the Assembly, a report on its work during the previous year. The report shall specify, in particular, the cases in which a State has not complied with the Court’s judgment’, and the Executive Council of the AU is required to ‘monitor … execution [of the judgment] on behalf of the Assembly’ (Protocol to the African Charter, Articles 31 and 29(2)). Beyond the information published by the Court in its activity reports, there is no one place where one can find what the State has done to respond to the judgment.

Following a commissioned study to examine what role it should play in monitoring its judgments,[I] the African Court proposed a Draft Framework For Reporting & Monitoring Execution Of Judgments And Other Decisions Of The African Court On Human And Peoples’ Rights (EX.CL/1126(XXXIV)Annex I). This proposes a monitoring role for the Court, under a newly established Monitoring Unit, whereby the State submits ‘execution reports’ to the Unit. The Court then uses these reports, along with information from other sources, including those other than the parties, to assess the level of compliance by the State, adopting a report on each case to that effect. It also proposes the possibility, in the event of lack of full compliance, of compliance hearings, on site visits and adoption of judgments or endorsement of a memorandum of understanding between the parties. The Framework sets out that the Court can issue a compliance judgment. It shares the monitoring of implementation by submitting compliance reports to the AU policy organs, this being considered firstly by the Permanent Representatives Committee, then the Executive Council and finally the Assembly. Support can be provided by the AU organs including through good offices, although ultimately information on the extent of compliance can be published by the Executive Council and Assembly, and the latter also has the possibility of invoking Article 23 ‘in deserving cases’. Encouraging States to adopt action plans, in line with the practice of the European system, is also identified in the Framework.

On the one hand, sharing the monitoring of implementation with political bodies can provide additional tools (as well as pressure) on States to respond. Certainly this is the model adopted by the Council of Europe whereby it is State diplomats in the Committee of Ministers and staff of the Department of Execution of Judgments that monitor implementation of the European Court of Human Rights’ judgments (Çali and Kok; Palmer; Committee of Ministers 2017). Yet this presumes respect for the independence of the judicial body by the political organs, something which is of considerable concern at present in the African system, as reflected in the adoption of the Executive Council decision in July 2018, which was seen as an AU policy organs’ interference in the independence of the African human rights system (EX.CL/Dec.1015(XXXIII); Biegon 2018). The Permanent Representatives’ Committee (PRC), Executive Council and Assembly need to be prepared to uphold the independence of the Court and properly assess State compliance, or lack thereof, with its judgments.

The Human Rights Law Implementation Project

The University of Bristol’s Human Rights Law Implementation Project tracked the implementation of decisions from a number of States in Africa, the Americas and Europe.[ii]Included among these decisions were App. No. 013/2011 – Abdoulaye Nikiema, Ernest Zongo, Blaise Ilboudo & Burkinabe Human and Peoples’ Rights Movement v Burkina Faso and App. No. 004/2013 – Lohe Issa Konaté v. Burkina Faso before the African Court. The cases related to the assassination of a journalist, Norbert Zongo, and companions, with the Court finding violations of the right to a fair trial and free expression, (Zongo et al) and criminalisation of defamation (Konaté). Burkina Faso was ordered to pay compensation; amend legislation on defamation; expunge the criminal convictions of Konaté; reopen investigations and bring the perpetrators to justice; and publish the judgment in various places at the national level. On the face of these, the State implemented the remedies quickly and in full. It paid the compensation within the six-month time limit; amended legislation; investigations were commenced and individuals prosecuted; and the judgment was published in the official gazette, a national newspaper and online.[iii] This positive record should be acknowledged. However, the factors determining how and why the State responded as it did are complex. These judgments were adopted in December 2014 (merits) and June 2015 and 2016 (reparations) in the wake of a transition government, as well as presidential and legislative elections. Legislation was indeed amended but there is evidence that national press associations played a key role in pushing for this, using the African Court ruling as a further tool (Interview A.1., 12 December 2017). Compensation was paid but domestic law and rules had to be followed to enable the money to reach the victim (Interview A.4., 13 December 2017). Therefore, even though this is a situation in which the government stated its intention to comply with the Court’s judgment and ruling, various other factors were crucial in facilitating and ensuring implementation.

Recommendations

What these judgments show, and our research supports, is that ensuring implementation is a multi-faceted process, requiring a ‘multi-dimensional’ approach which recognises the specificity and complexities of individual cases.[iv] For treaty bodies such as the African Court, this has a number of implications.

Firstly, although the African Court has ordered a variety of different types of reparations, it is by no means clear the basis on which it chooses the particular reparation. There does not appear to be a correlation between the violation of a particular right and a reparation being ordered. While this provides the African Court, and indeed the parties, with flexibility in calling for reparations which fit the context, it also fails to offer any guidance to the parties on what they can ask for. Some further assistance from the African Court, even if only to outline the possible reparations that it can order, may be useful.

Secondly, the African Court has been quite visible in providing the information on what the State has done to implement its judgements and rulings. However, this information is only available in its activity report. For those not familiar with how the Court works, the detail is hidden, not immediately visible from the front pages of the website. Our research suggests that one of the challenges with implementation of these types of international decisions is that there is limited visibility of their existence, let alone the measures taken by the State, at the national level (Murray 2019; Interview A.7. December 2017; Interview with civil society representative, Burkina Faso, July 2017; Interview B.2, July 2017; Interview with government official, Burkina Faso, December 2017). Key government authorities, parliamentarians and the judiciary, as well as national human rights institutions and civil society are not always aware of the judgment thus limiting the possibility of a ‘compliance coalition’ developing which can hold the State to account and work collectively towards implementation (Hillebrecht 2014; Hillebrecht 2012). The African Court can facilitate the visibility of its judgments at the national level by being more consistent in calling on the State, as it has done in some of its judgments and rulings (e.g. Mtikila v Tanzania, Ruling on Reparations, para 46), to publish the decision at the national level on a government website and in the national gazette. Furthermore, it could also require that information on the judgment is disseminated on social media. However, it is not just the judgment itself that may not be visible, but also the measures taken by the State to implement it. Consequently, the African Court can go further by requiring that the State publish information on the action it has taken to implement the decision. The African Court could also provide the tables in its activity reports elsewhere on its website to increase their visibility.

Thirdly, implementation is not automatic, even if the executive authorities are keen to comply with the Court’s judgment or ruling. For instance, compensation requires the involvement of other government authorities, such as the treasury or ministry of finance and budgetary considerations need to be taken into account. Amendment of legislation will necessitate the involvement of parliament, an entity independent of the executive and over whom it may have little control; and amendment or introduction of legislation in response to a judgment of the African Court will often be subject to the same rules and procedure as any other piece of legislation prompted by national actors. Release of an individual from custody, for example, will require some form of domestic process to be triggered in order for the judicial bodies to authorise. Some States have a government-committee or body which has the responsibility to coordinate implementation and identify the various elements of the State that need to take action.[v] Yet, these do not always operate transparently, may not have the broad composition needed to ensure dissemination of the decision or meet infrequently. Follow-up of the judgment can therefore slip between the cracks at the national level, with no one taking the lead on monitoring or ensuring its implementation. For most States, judgments from bodies such as the African Court are very few in number, and consequently a process is most likely often not in place at the national level to manage implementation. To address this, the African Court could, in each of its judgments or rulings on reparation call for the State to appoint within, say, a month, a focal point for that judgment who would take responsibility for coordinating its implementation. This would then provide the African Court with the key interlocutor with whom it could continue any discussions and obtain information on implementation and any challenges. Although the African Court has in the past asked States to identify focal points in the State ‘within the relevant Ministries, to facilitate communication between the Court and Member States (Report of the activities of the African Court 2016, paras 51 and 60(ix)), individual personnel changes can make continuity problematic. Requiring the State to nominate an individual or government department to take responsibility for that particular judgment or ruling at the time it is adopted may help to avoid such difficulties.

Lastly, the communication process is inherently adversarial, pitting the State authorities against the litigants and victims. Yet, what we found in our research is that often, post-decision or judgment, there is a need for some form of dialogue between the parties.[vi] If the reparation is left open-ended, then the State may need to negotiate with the victims as to what is required. The State equally may not always be clear precisely what is needed to implement the decision or may experience challenges in doing so. The African Court can be requested to interpret its judgment, an opportunity used by Tanzania and Côte d’Ivoire. This gave the Court the ability to clarify further what it required the State to do (Alex Thomas v Tanzania, 2017; APDH v Côte d’Ivoire, 2017; Abubakari v Tanzania, 2017). Whilst such mechanisms should not be used by the State to delay implementation or as a way of evading their responsibilities in providing relief to the victims, they are a form of conversation with the Court post-decision. In other cases in our Project, although not those of the African Court, we also saw that there may be greater consensus between the parties than each may be willing to admit in an adversarial process. Offering some possibility of dialogue between them post-decision can help to move implementation forward. As to whether the African Court, as a judicial body, can play this role needs to be carefully considered, and indeed lessons can be drawn from the experiences of the Inter-American Court on Human Rights in this regard (Inter-American Court, 2015; Rubio-Marín and Sandoval, 2011).

Whatever approach it adopts, the African Court may still wish to consider how it reflects the need for dialogue post-judgment in its rulings. For instance, it could ask the State to identify the focal point responsible for implementation and explicitly requiring that it engage with the victims in the implementation. Further, if there is a national committee such as a National Mechanism for Implementation, Reporting and Follow-up (NMIRF) then the African Court could explicitly recognise, in the reparations, the NMIRF’s role in implementation.

The implementation of the African Court’s judgments and rulings, as with those of any treaty body, is key to its legitimacy and effectiveness. The African Court’s willingness to develop a framework to clarify its role in monitoring how States respond to its decisions is very much to be welcomed.

[I] As requested by the Executive Council of the AU, Decisions Ex.CL/Dec.806 (XXIV) of January 2016 and Ex.CL/1012 (XXXIII) of June 2018, in which it asked the Court ‘to propose, for consideration by the PRC, a concrete reporting mechanism that will enable it to bring to the attention of relevant policy organs, situations of non-compliance and/or any other issues within its mandate, at any time, when the interest of justice so requires’.

[ii] www.bristol.ac.uk/hrlip. This was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and was in collaboration with the Universities of Bristol, Pretoria, and Middlesex and Essex as well as the Open Society Justice Initiative. Interviews were conducted with a wide range of stakeholders. These are anonymous, but referred to below by way of a letter and number, or position of the interviewee where appropriate.

[iii] African Court, Report on the activities of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (AfCHPR), 22-27 January 2017, EX.CL/999 (XXX), para 21(i). Interview A1, 12 December 2017. See also http://www.panapress.com/Burkina-Faso-to-compensate-victims-of-political-violence–13-455288-17-lang1-index.html; Interview A.11, December 2017.Interview A7, 23 December 2017; http://www.sig.bf/2015/09/decision-de-la-cour-africaine-des-droits-de-lhomme-et-des-peuples-sur-affaires-norbert-zongo/; List of issues in relation to the initial report of Burkina Faso, Addendum Replies of Burkina Faso to the list of issues*, [Date received: 1 April 2016], CCPR/C/BFA/Q/1/Add.1, 21 April 2016, para 103; Interview A1, 15 December 2017; Interview A.2, 15 December 2017; CHR, HRLIP, Workshop Report, Evaluation by Burkina Faso of their implementation of decisions made by International Human Rights Bodies, Ouagadougou, 27-28 November 2017; Press Freedom and Africa’s Regional Courts: A Positive Model for Transparency and Accountability’, Nani Jansen-Reventlow, http://www.doughtystreet.co.uk/news/article/press-freedom-and-africas-regional-courts-a-positive-model-for-transparency, 22 December 2016; Journal Official Special N°13, 15 October 2016.

[iv] See various articles in a Special Issue of the Journal of Human Rights Practice forthcoming, 2019.Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI). 2018. Strategic Litigation Impacts. Insights from Global Experience, Open Society Foundations, New York.

[v] E.g. Cameroon’s Inter-Ministerial Committee for monitoring the implementation ofrecommendations of the regional and international mechanisms, see R. Murray and C. de Vos, ‘Behind the State: domestic mechanisms and procedures for the implementation of human rights treaty body decisions’, Journal of Human Rights Practice, forthcoming 2019. Sometimes ‘National Mechanisms for Implementation, Reporting and Follow-up’ (NMIRF) or similar have this remit, see OHCHR, National Mechanisms for Reporting and Follow-up. A Practical Guide to Effective State Engagement with International Human Rights Mechanisms, OHCHR, New York and Geneva, 2016, HR/PUB/16/1; OHCHR, National Mechanisms for Reporting and Follow-up. A Study of State Engagement with International Human Rights Mechanisms, New York and Geneva, 2016, HR/PUB/16/1/Add.1; Universal Rights Group, Glion, Human Rights Dialogue, 2016, Human Rights Implementation, Compliance And The Prevention Of Violations: Turning International Norms Into Local Reality, Glion III, Universal Rights Group, 2016; Universal Rights Group, The Fifth Glion Human Rights Dialogue: The Place of Human Rights in a Reformed United Nations, Geneva, 2018.

[vi] C. Sandoval, P Leach and R Murray, ‘Monitoring, cajoling and promoting dialogue – what role for supranational human rights bodies in the implementation of individual decisions?’, Journal of Human Rights Practice, forthcoming 2019.